Similarly, Saltzman argues that Carver’s fiction, and indeed all minimalism, properly belongs in “another post-modern tributary” because it suspects “the referential adequacy of words” (9-10).

He contends that Carver’s texts “retain a flatness and an indeterminacy, an untranslated quality of experience that at the most allows for illustrative similes but will not resort to metaphorical mutation” (186-187). Chénetier speaks of Carver’s “refusal of metaphor” in charting a resolutely post-modern course for Carver. Saltzman, who has published the only book-length criticism of Carver to date.

#Raymond carver errand analysis free#

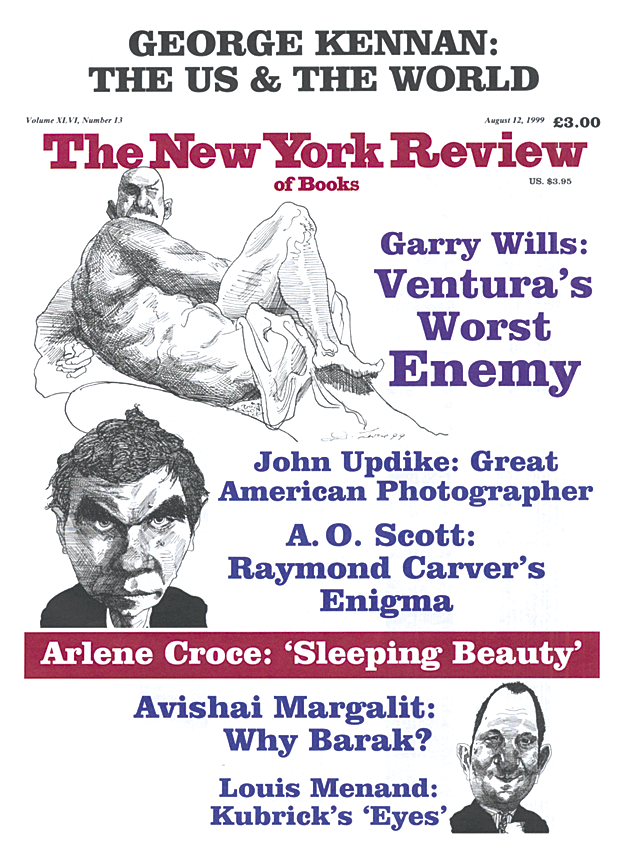

Only in “Where I’m Calling From” does Carver seem to surrender his overt rhetorical control and free his characters and his readers to grope together toward less tightly controlled themes.ĥTypical of those critics who have read Carver as a representative of postmodern distress are Marc Chénetier, who devoted a chapter to Carver in his collection of contemporary European criticism, and Arthur M. This examination shows that while Carver may have deepened his characterization, plots, and themes during his career, his rhetorical rein over objects and events – as well as over the destinies of his characters – has always been significant and deeply controlling, an aesthetic that is anything but either postmodern or humanistic.ĤIn fact, if a more humanistic Carver emerges in his later writings, the change does not come between the spare, tightly managed pessimism of “The Bath” and the almost sentimentally optimistic, but just as tightly managed, “A Small Good Thing” – which, like “Cathedral,” differs from its predecessor in tone and theme but not in aesthetic principle. One recent commentator, in fact, even posits a rather curious sort of “postmodern humanism” by which Carver is supposed to reject referential significance for a surface-bound postmodern fiction while at the same time he manages to reveal to his characters (and readers) not only “what a cathedral means,” but even the awareness of “spiritual being” (Brown 131, 136).ģA careful examination of Carver’s underlying theory of facts suggests an antidote to the current critical confusion. These readers suggest that Carver, with Cathedral, somehow traded in a rather battered minimalism for a shiny new humanist realism guaranteed to add new mileage to his writing. Much Carver criticism, therefore, finds in his minimal style evidence of postmodern distress, the refusal of the artist to bring a pattern-making vision to the debris of contemporary life (Chénetier 189 German and Bedell 257 Saltzman 9-10).ĢA second strain of Carver criticism grows out of that misreading and argues that Carver rejected his postmodern vehicle after he published What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (Facknitz, “The Calm” 387-388 Shute 1 Stull 6). Because so many Carver short stories present spare glimpses of characters snared in a tattered web of relationships and events whose significance they cannot understand, critics have often assumed that Carver, the artist, also refuses to endow the facts and events in his fiction with underlying significance. 1Raymond Carver’s literary reputation to date illustrates a rather common critical problem: the misreading of an author’s message for his underlying aesthetic theory.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)